這是你發表的第一篇文章。按一下「編輯」連結即可修改或刪除文章,或是開始撰寫新文章。你可以利用這篇文章告訴讀者這個網誌的建立原因,以及網誌的未來計畫。

這是你發表的第一篇文章。按一下「編輯」連結即可修改或刪除文章,或是開始撰寫新文章。你可以利用這篇文章告訴讀者這個網誌的建立原因,以及網誌的未來計畫。

While noteworthy that 73 percent of political nominees donated, it is perhaps more surprising that 27 percent did not. The common assumption seems to be that those who become ambassadors without first entering the Foreign Service must have paid their way into office. The surprise largely dissipates, however, upon closer scrutiny. A clear majority of the 27 percent are individuals with high-level experience in the executive branch or Congress—such as Deputy Chief of Staff at the White House, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff,

and members of the House or Senate—all of whom appear capable of using their influence or personal connections to the president, rather than financial support, to secure a nomination. […]

The picture for career nominees is much different. From 1980 to 2019, only 5 percent personally contributed, and their contributions averaged only thirty-three dollars. […

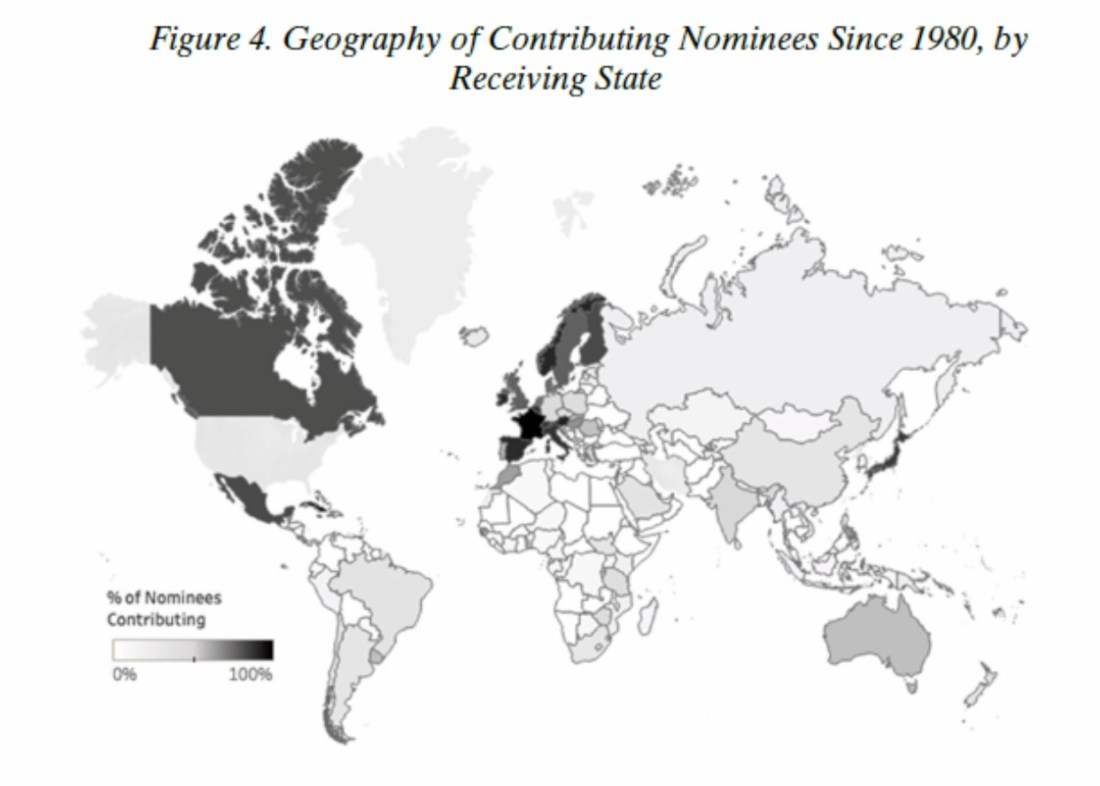

Another way to think about the role of money is to examine whether campaign contributions affect bilateral relationships to different degrees. Figure 4 addresses this issue by depicting, for each state, the percentage of the nominees who made financial contributions to the nominating president, with values ranging from 0 percent (white) to 100 percent (black). The data establish that donors were most common among nominees to politically stable and economically developed countries, particularly in Western Europe.

This doesn’t, of course, answer whether this is ethical or a good idea, other than to justify it with tradition.

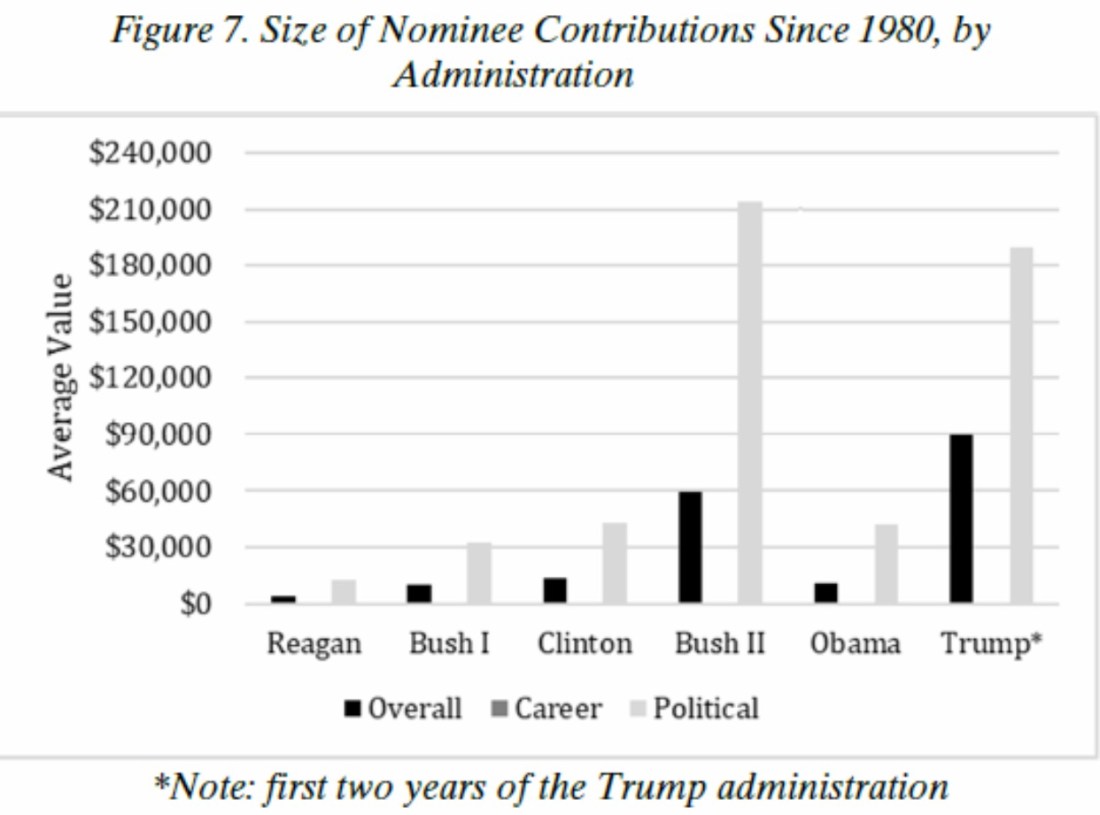

There are also some stats over time on contributions by would-be ambassadors:

This pattern (of contributions) is a bit different than merely looking at the percentage of political appointees. G.W. Bush and Trump are clearly outliers here with much larger campaign contributions (from would-be ambassadors) than the rest of the presidents since Reagan.

Also Sondland is not actually the largest such example from the Trump era:

You must be logged in to post a comment.